Insight

Intro to AI for Robotics

Jan 6, 2026

What’s a robot, anyway?

As 2025 closes out, there’s a lot of talk of humanoids - more precisely, bipeds - two-legged robots that are built to roughly resemble humans. But bipeds are really just surface-level hype: there are many other very useful form factors that are likely to ship first, if only because adding legs to your robot triples the cost.

We’ve dubbed the current wave of innovation “AI-native robotics”, if simply for lack of a better catch-all that doesn’t presuppose a form factor or application. Briefly speaking, these are robots characterized by closed-loop, vision-first control, model-based (neural or otherwise) planning algorithms, and a certain type of hardware design paradigm that favors speed and cost over positioning accuracy or raw force output.

Why now?

Simple: a bunch of things came together at the right time to make this all possible. A big part comes down to more accessible hardware - modern robots are built out of a weird mash of parts from drones, smart home, power tools, and tablets. It turns out that making all of these parts into a robot is not too hard, and once MIT showed the world it was possible, an explosion of commercially available robots appeared over the next few years.

Likewise, large model-based algorithms reached their zenith in 2023 with GPT-3, which demonstrated that well-placed use of mathematical models had immense commercial value. In the two years that followed, a flurry of work into modeling algorithms demonstrated that the one remaining problem in robotics was solvable using machine learning.

So, what’s that one problem anyway?

User interface. Right now, robots have to be individually programmed by engineers to complete tasks, and the tasks themselves need to be on well-defined rails - for example, slight changes to lighting, color, or shape will likely throw off a program. This constrains robots to factory environments where engineers have 100% control of the tasks, lighting, background, etc.

In order to bring robots into more mainstream applications, we need a user interface that can handle a high degree of “fuzziness”. This doesn’t necessarily mean natural language - maybe robots will be useful enough that users can handle a certain degree of learning, or maybe we’ll have an app store-like model where users can buy “personalities” for their robots. What it does mean, though, is that whether through apps or custom blocks, the result should be able to handle changes in color, brand, lighting, placement, and so on - an apple is an apple regardless of its color, and pants are pants no matter what style they’re in.

You might be thinking to yourself, “hey, that sounds like an AI agent”. And you’d be right…

Robots and learning

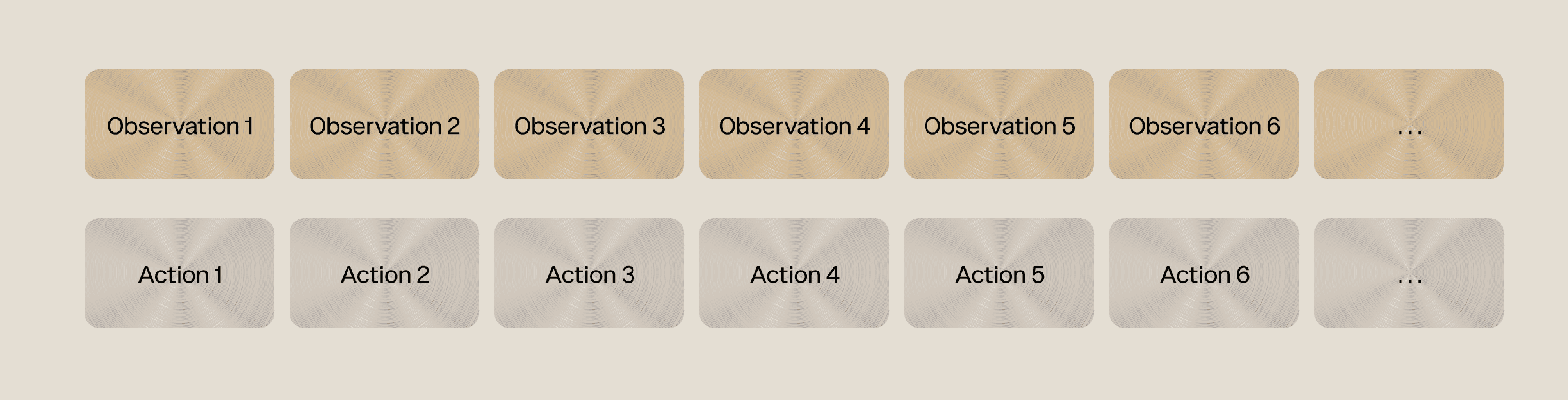

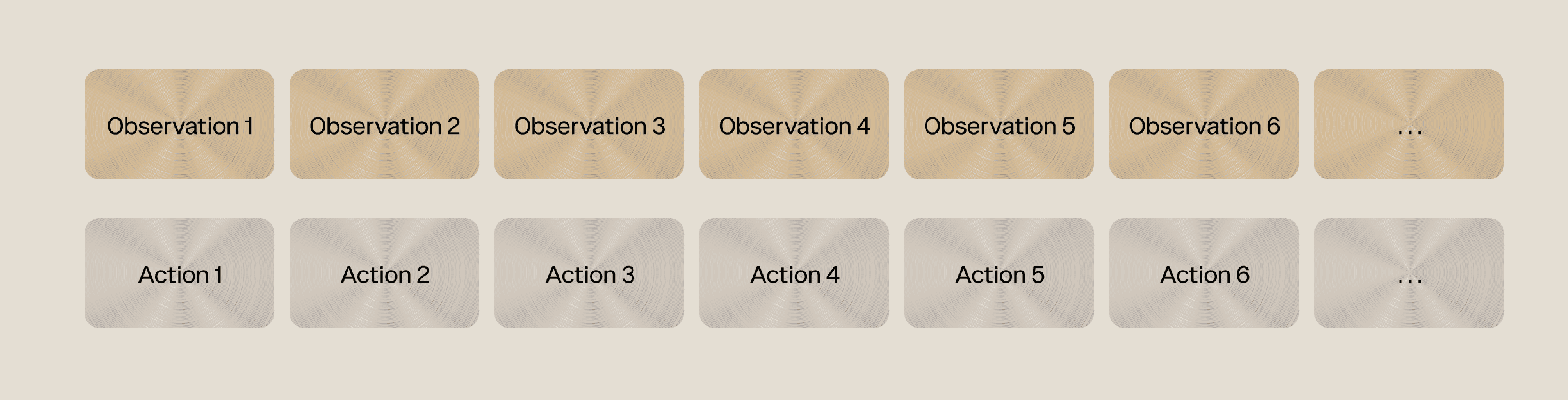

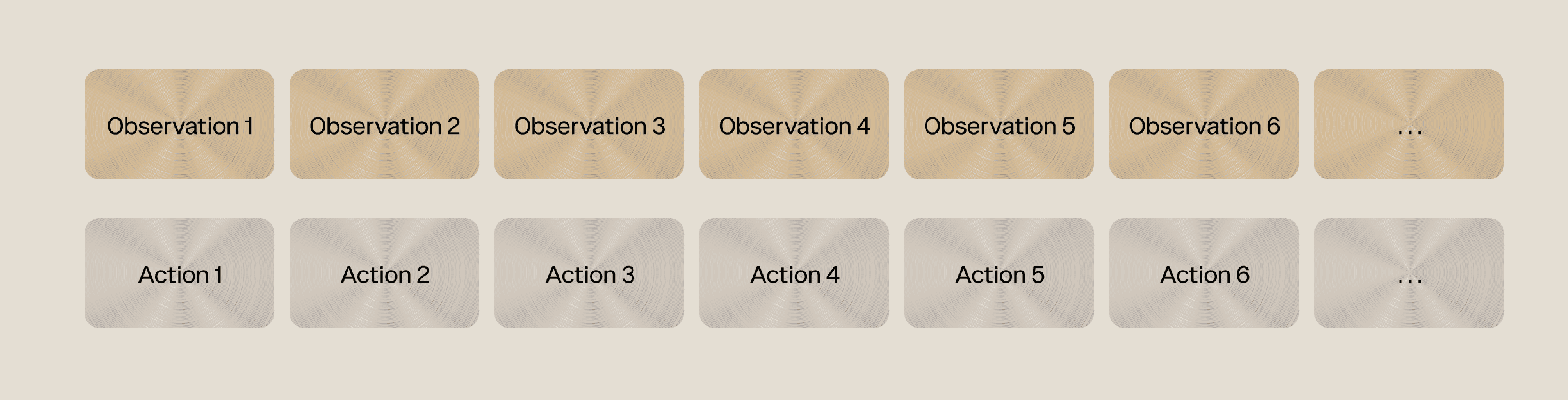

2025’s AI-native robotics all focus on some flavor of end to end learning. That is, during deployment, the loop looks like this:

Sensor observations → Planned actions → Physical interactions → More sensor observations

The robot continuously observes its surroundings (usually with cameras, but there are a few other sensors as well), the software takes those observations and generates a plan for what actions to take to achieve the goal, the robot begins executing those actions, then observes how its surroundings change and begins the cycle again. This loop happens several times per second, and because of the plan-act-observe structure, allows the robot to react to changes and mistakes along the way.

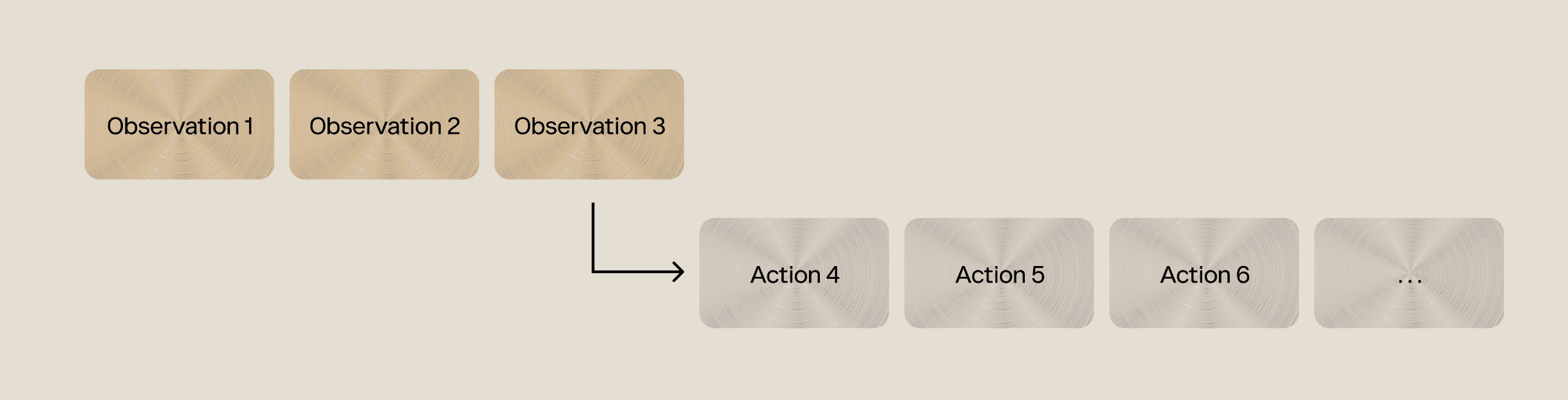

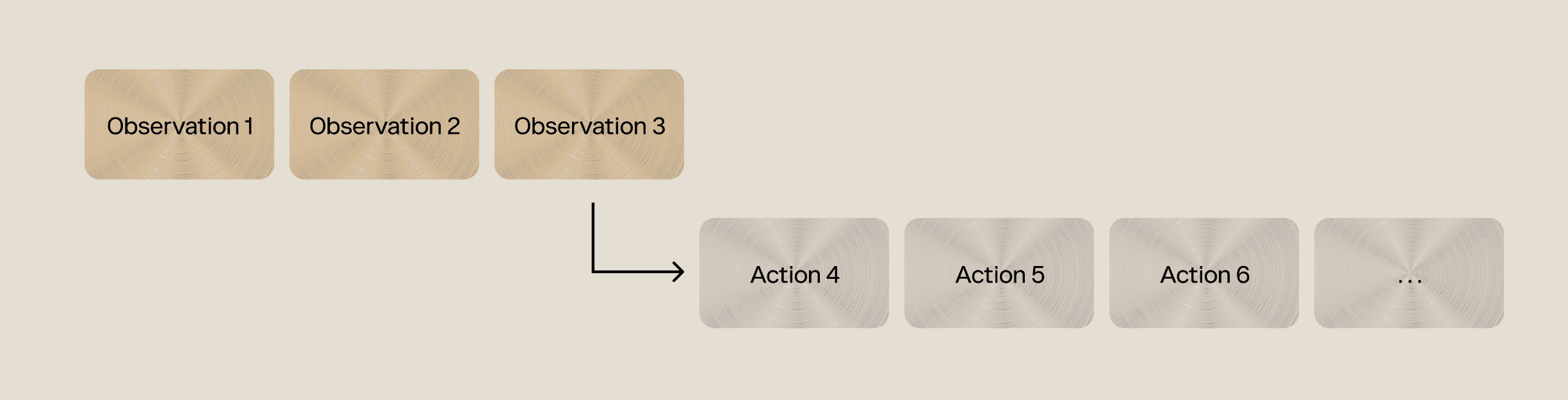

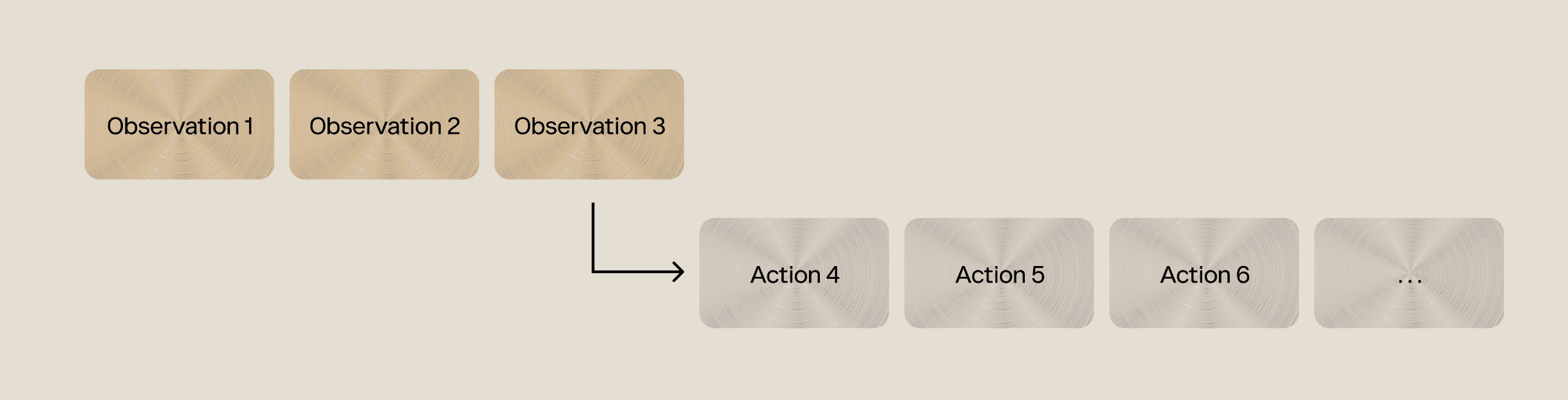

To train the robot, we first collect traces of observations and actions from the robot completing some tasks.

Then, we train an AI model on this data, to generate future actions from past observations. That’s all there is to it! The model looks a bit like an image generation model, so most of the tricks from the past two years there work for robotics too.

It’s (mostly) a data problem

Because robot models look like image generation models and image generation models have had billions of dollars poured into them, the underlying AI research is “mostly solved” - now that AI-native robotics is a year and a bit more old, the general consensus is that the underlying data split, not the model architecture, drives performance. There are a lot of architectural tricks, but many of these are simply to deal with the lack of data.

There are a number of ways to collect training data, but by and large, most of the industry does it by having humans remote-control robots (teleoperation), then collecting videos and other sensor data (motor angles, forces, …) during the remote control process. Then this data goes into the training loop above and is used to create models that predict future actions from past observations.

A small demo

Here’s a small demo we put together to illustrate the model training loop. The top video is a montage of different data samples we collected, the bottom video is the same robot autonomously completing tasks similar to the ones in the training data.

We cheated a bit here, of course - we fine tuned a model that had already previously seen a few thousand hours of training data to save time. With only a few examples, the model can be adapted to work in previously unseen environments. As we add more data to the mix, the model learns to interact with more and more different environments. The idea is if we add a ton of data, the model gains LLM-like capabilities and will “discover” how to mix up previously seen data to generate entirely new solutions to tasks and environments it has never seen before.

What’s a robot good for?

There’s way more confusion here than there should be. You’ll see a lot of demos of acrobatics: dancing, flips and rolls in every direction, recovery from accidents, etc. These are mostly from hardware manufacturers, who are eager to show off the power of their latest robots, and from academic institutions, where highly dynamic motion is an active and exciting field of frontier research.However, as cool as these demos are, they don’t really represent real use cases - you probably don’t want your home/restaurant/factory robot randomly doing a barrel roll or fighting back against humans.

The actual use cases split down the middle depending on where you are. Over here in the United States (and generally applicable to western Europe and the more affluent Asian countries), the vision is to automate away the sundry tasks of day to day life and business: restocking shelves, cleaning offices, making fast food, last mile delivery, and so on. These use cases broadly encompass all domestic and a large chunk of commercial applications; while manufacturing is a light-touch area of interest for US-based companies, traditional manufacturing falls in the domain of pre-AI robotics and doesn’t really benefit from recent developments.

In manufacturing powerhouse regions such as Southeast Asia, and China, the situation flips. You’d be deranged to be building $50,000 USD machines to sweep the floors - the depreciated yearly cost of the machine would cost more than a person - but there is a huge focus on enabling advanced manufacturing with robotics. Especially in frontier technology (aerospace, scientific, semiconductor, defense, …) a huge part of the pipeline is skilled technicians, who are error-prone and hard to scale. Businesses in these regions see robotics as a way to effectively compete in the global market for high-margin, strategically important industries without having to train up huge workforces of skilled labor.

More to explore

Insight

Intro to AI for Robotics

Jan 6, 2026

What’s a robot, anyway?

As 2025 closes out, there’s a lot of talk of humanoids - more precisely, bipeds - two-legged robots that are built to roughly resemble humans. But bipeds are really just surface-level hype: there are many other very useful form factors that are likely to ship first, if only because adding legs to your robot triples the cost.

We’ve dubbed the current wave of innovation “AI-native robotics”, if simply for lack of a better catch-all that doesn’t presuppose a form factor or application. Briefly speaking, these are robots characterized by closed-loop, vision-first control, model-based (neural or otherwise) planning algorithms, and a certain type of hardware design paradigm that favors speed and cost over positioning accuracy or raw force output.

Why now?

Simple: a bunch of things came together at the right time to make this all possible. A big part comes down to more accessible hardware - modern robots are built out of a weird mash of parts from drones, smart home, power tools, and tablets. It turns out that making all of these parts into a robot is not too hard, and once MIT showed the world it was possible, an explosion of commercially available robots appeared over the next few years.

Likewise, large model-based algorithms reached their zenith in 2023 with GPT-3, which demonstrated that well-placed use of mathematical models had immense commercial value. In the two years that followed, a flurry of work into modeling algorithms demonstrated that the one remaining problem in robotics was solvable using machine learning.

So, what’s that one problem anyway?

User interface. Right now, robots have to be individually programmed by engineers to complete tasks, and the tasks themselves need to be on well-defined rails - for example, slight changes to lighting, color, or shape will likely throw off a program. This constrains robots to factory environments where engineers have 100% control of the tasks, lighting, background, etc.

In order to bring robots into more mainstream applications, we need a user interface that can handle a high degree of “fuzziness”. This doesn’t necessarily mean natural language - maybe robots will be useful enough that users can handle a certain degree of learning, or maybe we’ll have an app store-like model where users can buy “personalities” for their robots. What it does mean, though, is that whether through apps or custom blocks, the result should be able to handle changes in color, brand, lighting, placement, and so on - an apple is an apple regardless of its color, and pants are pants no matter what style they’re in.

You might be thinking to yourself, “hey, that sounds like an AI agent”. And you’d be right…

Robots and learning

2025’s AI-native robotics all focus on some flavor of end to end learning. That is, during deployment, the loop looks like this:

Sensor observations → Planned actions → Physical interactions → More sensor observations

The robot continuously observes its surroundings (usually with cameras, but there are a few other sensors as well), the software takes those observations and generates a plan for what actions to take to achieve the goal, the robot begins executing those actions, then observes how its surroundings change and begins the cycle again. This loop happens several times per second, and because of the plan-act-observe structure, allows the robot to react to changes and mistakes along the way.

To train the robot, we first collect traces of observations and actions from the robot completing some tasks.

Then, we train an AI model on this data, to generate future actions from past observations. That’s all there is to it! The model looks a bit like an image generation model, so most of the tricks from the past two years there work for robotics too.

It’s (mostly) a data problem

Because robot models look like image generation models and image generation models have had billions of dollars poured into them, the underlying AI research is “mostly solved” - now that AI-native robotics is a year and a bit more old, the general consensus is that the underlying data split, not the model architecture, drives performance. There are a lot of architectural tricks, but many of these are simply to deal with the lack of data.

There are a number of ways to collect training data, but by and large, most of the industry does it by having humans remote-control robots (teleoperation), then collecting videos and other sensor data (motor angles, forces, …) during the remote control process. Then this data goes into the training loop above and is used to create models that predict future actions from past observations.

A small demo

Here’s a small demo we put together to illustrate the model training loop. The top video is a montage of different data samples we collected, the bottom video is the same robot autonomously completing tasks similar to the ones in the training data.

We cheated a bit here, of course - we fine tuned a model that had already previously seen a few thousand hours of training data to save time. With only a few examples, the model can be adapted to work in previously unseen environments. As we add more data to the mix, the model learns to interact with more and more different environments. The idea is if we add a ton of data, the model gains LLM-like capabilities and will “discover” how to mix up previously seen data to generate entirely new solutions to tasks and environments it has never seen before.

What’s a robot good for?

There’s way more confusion here than there should be. You’ll see a lot of demos of acrobatics: dancing, flips and rolls in every direction, recovery from accidents, etc. These are mostly from hardware manufacturers, who are eager to show off the power of their latest robots, and from academic institutions, where highly dynamic motion is an active and exciting field of frontier research.However, as cool as these demos are, they don’t really represent real use cases - you probably don’t want your home/restaurant/factory robot randomly doing a barrel roll or fighting back against humans.

The actual use cases split down the middle depending on where you are. Over here in the United States (and generally applicable to western Europe and the more affluent Asian countries), the vision is to automate away the sundry tasks of day to day life and business: restocking shelves, cleaning offices, making fast food, last mile delivery, and so on. These use cases broadly encompass all domestic and a large chunk of commercial applications; while manufacturing is a light-touch area of interest for US-based companies, traditional manufacturing falls in the domain of pre-AI robotics and doesn’t really benefit from recent developments.

In manufacturing powerhouse regions such as Southeast Asia, and China, the situation flips. You’d be deranged to be building $50,000 USD machines to sweep the floors - the depreciated yearly cost of the machine would cost more than a person - but there is a huge focus on enabling advanced manufacturing with robotics. Especially in frontier technology (aerospace, scientific, semiconductor, defense, …) a huge part of the pipeline is skilled technicians, who are error-prone and hard to scale. Businesses in these regions see robotics as a way to effectively compete in the global market for high-margin, strategically important industries without having to train up huge workforces of skilled labor.

Insight

Intro to AI for Robotics

Jan 6, 2026

What’s a robot, anyway?

As 2025 closes out, there’s a lot of talk of humanoids - more precisely, bipeds - two-legged robots that are built to roughly resemble humans. But bipeds are really just surface-level hype: there are many other very useful form factors that are likely to ship first, if only because adding legs to your robot triples the cost.

We’ve dubbed the current wave of innovation “AI-native robotics”, if simply for lack of a better catch-all that doesn’t presuppose a form factor or application. Briefly speaking, these are robots characterized by closed-loop, vision-first control, model-based (neural or otherwise) planning algorithms, and a certain type of hardware design paradigm that favors speed and cost over positioning accuracy or raw force output.

Why now?

Simple: a bunch of things came together at the right time to make this all possible. A big part comes down to more accessible hardware - modern robots are built out of a weird mash of parts from drones, smart home, power tools, and tablets. It turns out that making all of these parts into a robot is not too hard, and once MIT showed the world it was possible, an explosion of commercially available robots appeared over the next few years.

Likewise, large model-based algorithms reached their zenith in 2023 with GPT-3, which demonstrated that well-placed use of mathematical models had immense commercial value. In the two years that followed, a flurry of work into modeling algorithms demonstrated that the one remaining problem in robotics was solvable using machine learning.

So, what’s that one problem anyway?

User interface. Right now, robots have to be individually programmed by engineers to complete tasks, and the tasks themselves need to be on well-defined rails - for example, slight changes to lighting, color, or shape will likely throw off a program. This constrains robots to factory environments where engineers have 100% control of the tasks, lighting, background, etc.

In order to bring robots into more mainstream applications, we need a user interface that can handle a high degree of “fuzziness”. This doesn’t necessarily mean natural language - maybe robots will be useful enough that users can handle a certain degree of learning, or maybe we’ll have an app store-like model where users can buy “personalities” for their robots. What it does mean, though, is that whether through apps or custom blocks, the result should be able to handle changes in color, brand, lighting, placement, and so on - an apple is an apple regardless of its color, and pants are pants no matter what style they’re in.

You might be thinking to yourself, “hey, that sounds like an AI agent”. And you’d be right…

Robots and learning

2025’s AI-native robotics all focus on some flavor of end to end learning. That is, during deployment, the loop looks like this:

Sensor observations → Planned actions → Physical interactions → More sensor observations

The robot continuously observes its surroundings (usually with cameras, but there are a few other sensors as well), the software takes those observations and generates a plan for what actions to take to achieve the goal, the robot begins executing those actions, then observes how its surroundings change and begins the cycle again. This loop happens several times per second, and because of the plan-act-observe structure, allows the robot to react to changes and mistakes along the way.

To train the robot, we first collect traces of observations and actions from the robot completing some tasks.

Then, we train an AI model on this data, to generate future actions from past observations. That’s all there is to it! The model looks a bit like an image generation model, so most of the tricks from the past two years there work for robotics too.

It’s (mostly) a data problem

Because robot models look like image generation models and image generation models have had billions of dollars poured into them, the underlying AI research is “mostly solved” - now that AI-native robotics is a year and a bit more old, the general consensus is that the underlying data split, not the model architecture, drives performance. There are a lot of architectural tricks, but many of these are simply to deal with the lack of data.

There are a number of ways to collect training data, but by and large, most of the industry does it by having humans remote-control robots (teleoperation), then collecting videos and other sensor data (motor angles, forces, …) during the remote control process. Then this data goes into the training loop above and is used to create models that predict future actions from past observations.

A small demo

Here’s a small demo we put together to illustrate the model training loop. The top video is a montage of different data samples we collected, the bottom video is the same robot autonomously completing tasks similar to the ones in the training data.

We cheated a bit here, of course - we fine tuned a model that had already previously seen a few thousand hours of training data to save time. With only a few examples, the model can be adapted to work in previously unseen environments. As we add more data to the mix, the model learns to interact with more and more different environments. The idea is if we add a ton of data, the model gains LLM-like capabilities and will “discover” how to mix up previously seen data to generate entirely new solutions to tasks and environments it has never seen before.

What’s a robot good for?

There’s way more confusion here than there should be. You’ll see a lot of demos of acrobatics: dancing, flips and rolls in every direction, recovery from accidents, etc. These are mostly from hardware manufacturers, who are eager to show off the power of their latest robots, and from academic institutions, where highly dynamic motion is an active and exciting field of frontier research.However, as cool as these demos are, they don’t really represent real use cases - you probably don’t want your home/restaurant/factory robot randomly doing a barrel roll or fighting back against humans.

The actual use cases split down the middle depending on where you are. Over here in the United States (and generally applicable to western Europe and the more affluent Asian countries), the vision is to automate away the sundry tasks of day to day life and business: restocking shelves, cleaning offices, making fast food, last mile delivery, and so on. These use cases broadly encompass all domestic and a large chunk of commercial applications; while manufacturing is a light-touch area of interest for US-based companies, traditional manufacturing falls in the domain of pre-AI robotics and doesn’t really benefit from recent developments.

In manufacturing powerhouse regions such as Southeast Asia, and China, the situation flips. You’d be deranged to be building $50,000 USD machines to sweep the floors - the depreciated yearly cost of the machine would cost more than a person - but there is a huge focus on enabling advanced manufacturing with robotics. Especially in frontier technology (aerospace, scientific, semiconductor, defense, …) a huge part of the pipeline is skilled technicians, who are error-prone and hard to scale. Businesses in these regions see robotics as a way to effectively compete in the global market for high-margin, strategically important industries without having to train up huge workforces of skilled labor.